There is a considerable amount of controversy surrounding Metis citizenship since the tabling of Bill C-53 by the Trudeau Liberals in 2023-2024, which recognized and created a tax treaty between the 3 Metis Nations of Alberta, Saskatchewan and Ontario, excluding all others. The bill has sparked significant controversy, particularly concerning its implications for First Nations and within the Métis community itself. I would like to use the investigation into my heritage to expose an issue which I feel has been created by the current Liberal administration and which is only serving to further divide the people of Canada through its mismanagement.

First Nations’ Reaction:

Many First Nations, especially in Ontario, have expressed strong opposition to Bill C-53. The Chiefs of Ontario have stated that they “do not recognize the Métis Nation of Ontario as a legitimate organization” and argue that passing the bill would infringe upon their inherent and treaty rights. They contend that the Métis Nation of Ontario represents communities lacking a historical basis and that do not meet the legal threshold for Indigenous rights. Concerns have also been raised about the potential overlap and confusion between Métis and First Nations membership lists, with some individuals appearing in both groups. Critics argue that some ancestors claimed by current Métis members were officially First Nation individuals, leading to disputes over identity and rights. Read the Anishinabek Nation position on the Métis Nation of Ontario.

Métis Community Reaction:

Within the Métis community, reactions to Bill C-53 are mixed. The Métis National Council (MNC) and its member organizations, such as the Métis Nation of Alberta, have expressed support for the bill, viewing it as a step toward self-determination and recognition of Métis rights.

However, internal disputes have arisen, particularly concerning the inclusion of the Métis Nation of Ontario (MNO). The Manitoba Métis Federation (MMF) withdrew from the MNC in 2021, citing disagreements over the MNO’s recognition of certain communities outside the traditional Métis homeland. In April 2024, the Métis Nation–Saskatchewan (MNS) also withdrew its support for Bill C-53, criticizing the bill’s “one-size-fits-all” approach and expressing concerns over the inclusion of the Metis Nation Ontario. Subsequently, Metis Nation Saskatechewan announced its withdrawal and that it would seek its own distinct path toward self-governance.

It is important to note that The Métis National Council (MNC) and Métis Nation of Ontario (MNO) appear to be one in the same entity, that has made some kind of power play in an attempt to control the narrative for all Metis Nations in Canada.

Due to these controversies and the withdrawal of support from several Metis Nations, the federal government has paused the progression of Bill C-53. Meanwhile, the Assembly of First Nations (AFN) has reaffirmed its call for the immediate withdrawal of Bill C-53, stating that it fails to address First Nations’ concerns and could undermine their rights.

First Nations Citizenship

Now, the fight for recognition of First Nations ancestry has been ongoing since Canada was colonized and often was granted only at the whim of First Nations chiefs who could deny citizenship for any reason. First Nations citizenship in Canada has historically been governed by the Indian Act, which imposed strict rules on who was legally recognized as a “Status Indian.”

The Indian Act was first written and passed into law in 1876 by the Government of Canada. It consolidated earlier colonial laws related to Indigenous peoples and established federal control over many aspects of First Nations life, including governance, land, status, and culture.

Prior to 1985, Indigenous women who married non-Indigenous men automatically lost their Indian status and could no longer pass it to their children, while Indigenous men who married non-Indigenous women retained their status and conferred it to their spouses and children. This gender-based discrimination was challenged for decades, leading to the passage of Bill C-31 in 1985, which amended the Indian Act to restore status to women and their descendants who had been forcibly enfranchised through marriage. However, the amendment created new generational cutoffs, leading to ongoing disputes about status eligibility. Further amendments, such as Bill C-3 (2011) and Bill S-3 (2017–2019), have since addressed some remaining inequities, but issues of exclusion and discrimination in First Nations citizenship laws continue to be a source of controversy and it is no surprise that the Metis nations struggle with the same. The difference of course is the legal definition vs the ancestral bloodlines.

My Heritage

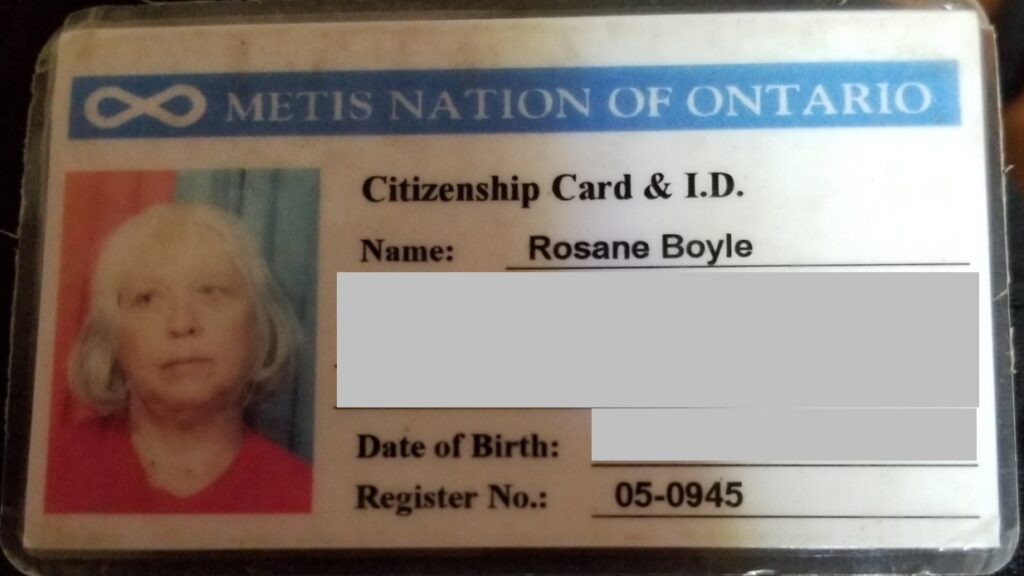

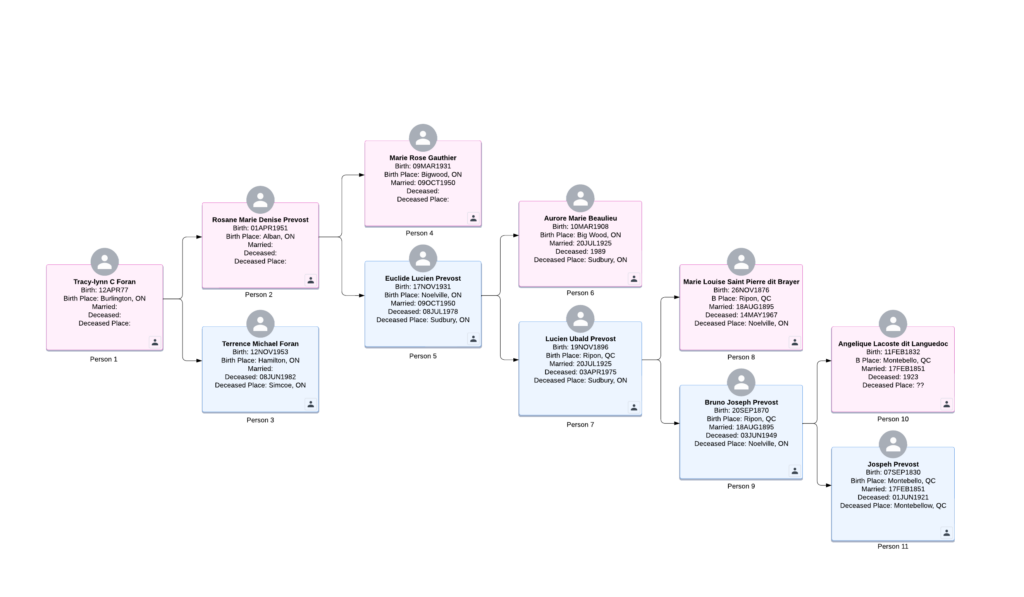

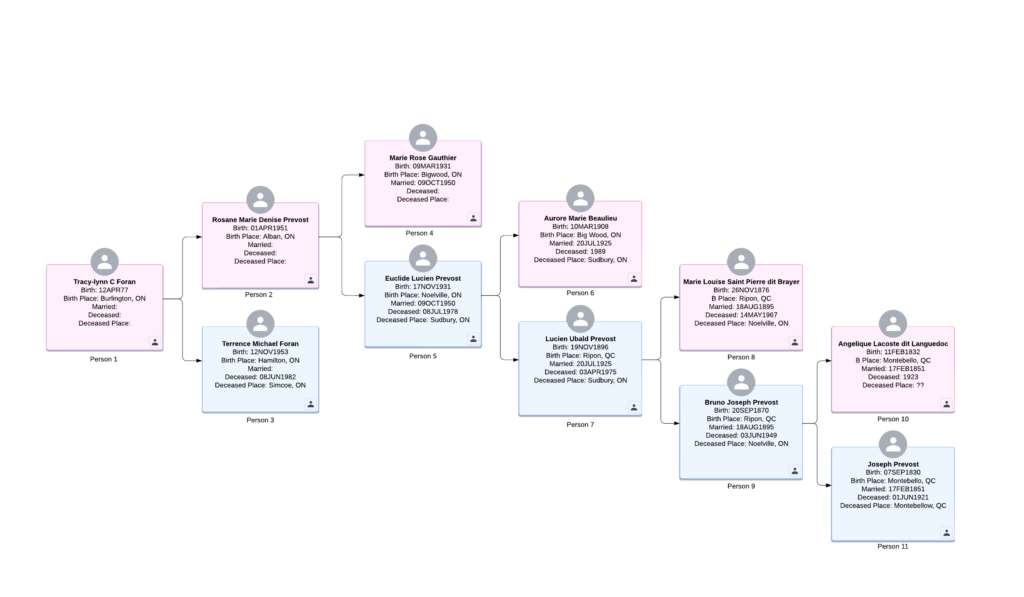

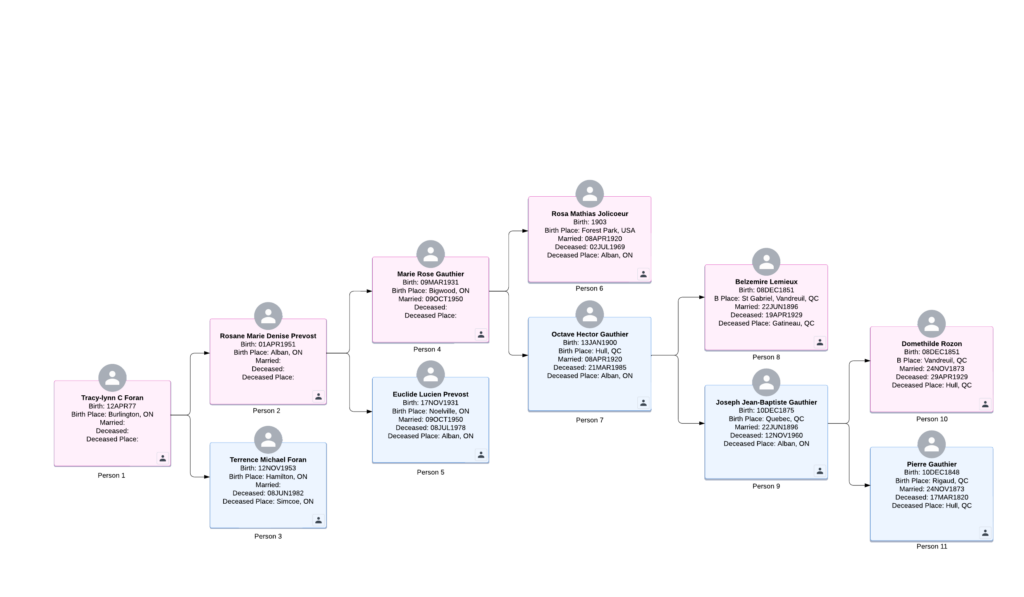

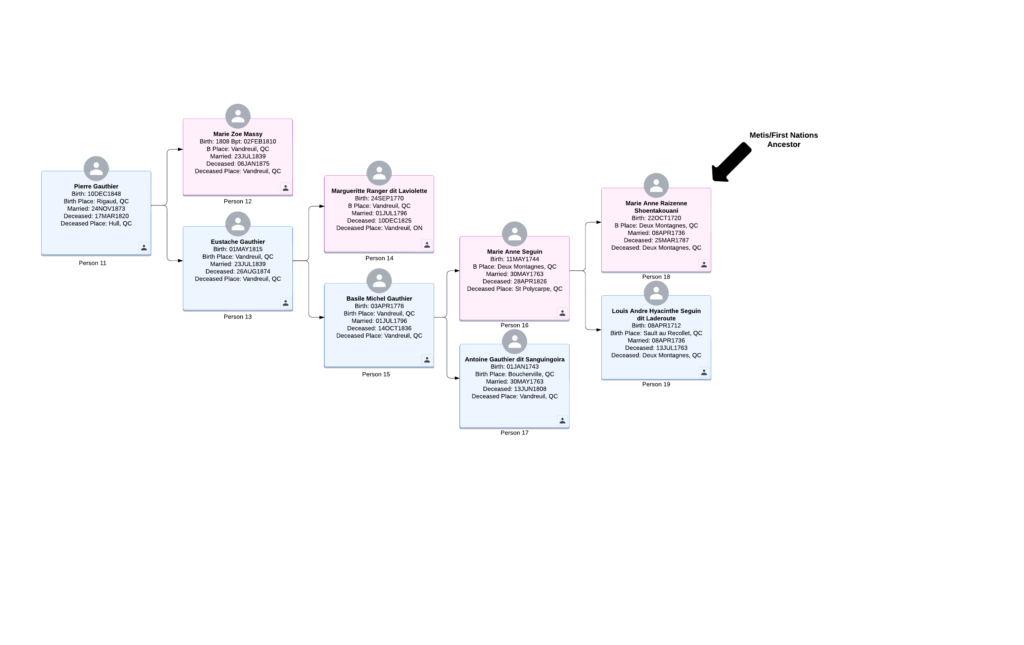

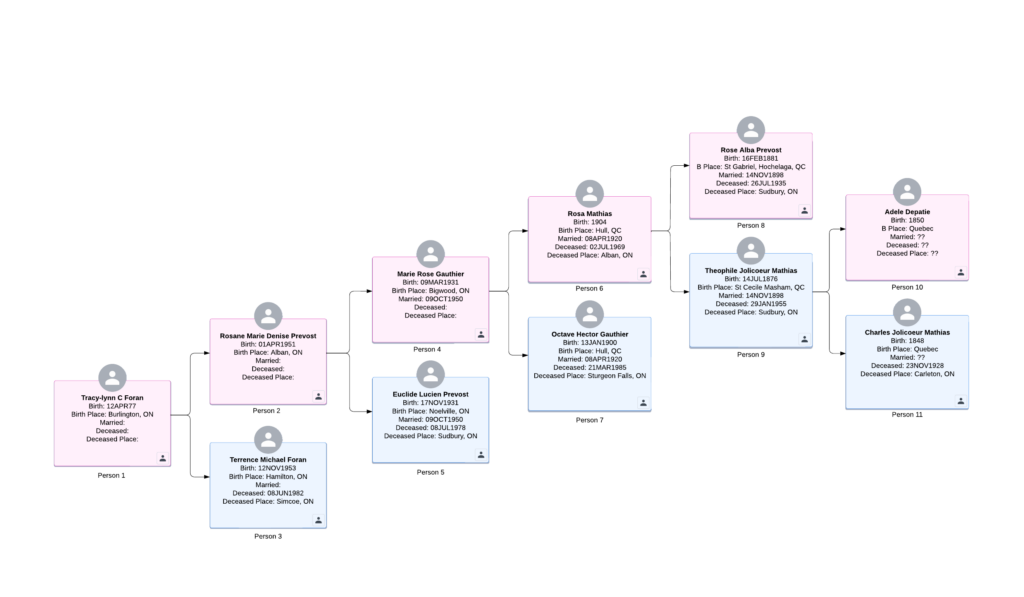

My mother held Metis citizenship for many years, but at some point the definition changed and her Metis citizenship was revoked. To my knowledge she is working to get it back and I have equally been doing my own research to help her. Based on my own research, I have located as many as 9 bloodlines which potentially trace back to First Nation ancestry, of which 4 bloodlines have been traced and are posted below. My mother’s skin is brown and she clearly presents as First Nations. I can also personally attest to a unique upbringing which was very closely associated to hunting, trapping, fishing, wood carving, hand beading and other activities.

This is over 30 years old and I still have it.

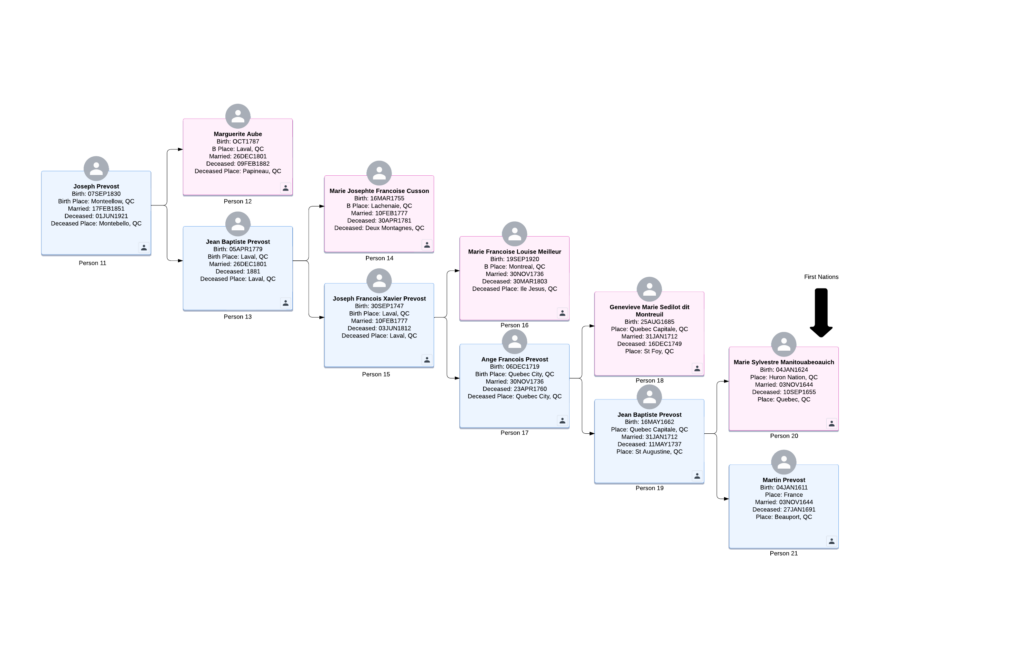

First Nations Ancestor #1 – Marie Olivier Syvestre Manitouabewich (Huron/Algonquin)

This is the line that my mother obtained her Metis status under originally which has since been rejected as a Metis line with the new revised definitions which only grants Metis citizenship to the direct ancestors of the Louis Riel settlement. In much the same way that women who married off the reserve were rejected from having First Nations citizenship even if full blooded. Read the history of this line here.

First Nations Ancestor #2 – Marie Anne Giroux (Huron/Algonquin)

This is a second line, tracing back to the same ancestry as the first line, via brothers a few generations removed. Read the history of this line here.

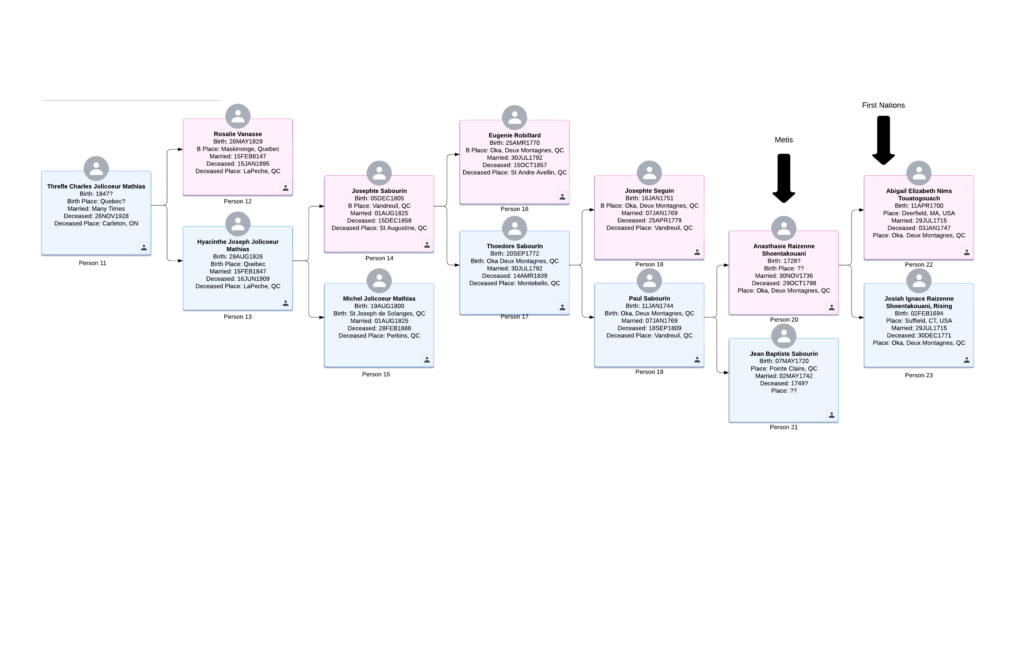

First Nations Ancestor #3 – Marie Anne Raizenne

This is a line which has been traced more recently and traces back to the Shoentakouani tribe, a tribe which crossed the US/Canada border. View the official documentation of this line here which shows it to be a recognized Metis community at the time this document was created.

First Nations Ancestor #4 – Anasthasie Raizenne

This is a second line which traces back to the Shoentakouani tribe, but to a different set of ancestors. View the official documentation of this line here which shows it to be a recognized Metis community at the time of creating this document.

Disclaimer

I have never sought to claim or benefit from my First Nations ancestry—in fact, for much of my life, I felt the need to downplay it due to the discrimination my family experienced, particularly because of my mother’s skin color. I speak about it now only because, given my involvement in politics, it is bound to surface, and because I was already working to support my mother in reclaiming her rightful status. This is not about personal gain, but about transparency, spreading awareness and ensuring fairness.

Further Investigation

It is important to note that all of these First Nations blood lines trace to women who married away from their tribes and thereby were no longer recognized as First Nations, despite being born First Nations. In total there are potentially 9 bloodlines, which show that our family has been interbreeding with mixed First Nations, in this region, for generations. Given the number of bloodlines in my family tree, it could be argued that a very quiet and unassuming Metis community did migrate from Quebec and establish itself in the Greater Sudbury area. However, I am not a historian or genealogist and will leave this argument for those with more skill and knowledge in this area. The additional lines which still require investigation include:

- Louis Brais dit Labonte 1754-1834

- Marie Rose Brabant dit Lamothe 1764-1838

- Marie-Anne Bouchard 1699-1760

- Marie Pelagies Fradet 1760-1821

- Pierre Cadieux 1666-1727 (Muskrat Metis?)

References:

- Indian Act

- Bill C-53

- Background on Indian Registration

- What is Bill C-31 & Bill C-3

- ‘Kill the bill on the hill’: First Nations in Ontario voice their opposition to Métis self government bill – APTN News

- The government’s bill on Métis rights has ignited a messy fight with First Nations: Ken Coates in the Globe and Mail – MacDonald Laurier

- Bill C-53 is Reconciliation in Action – Metis Nation Alberta

- Metis National Council – Wikipedia

- Feds pause proposed law that would recognize Métis in Ontario, Alberta and Saskatchewan